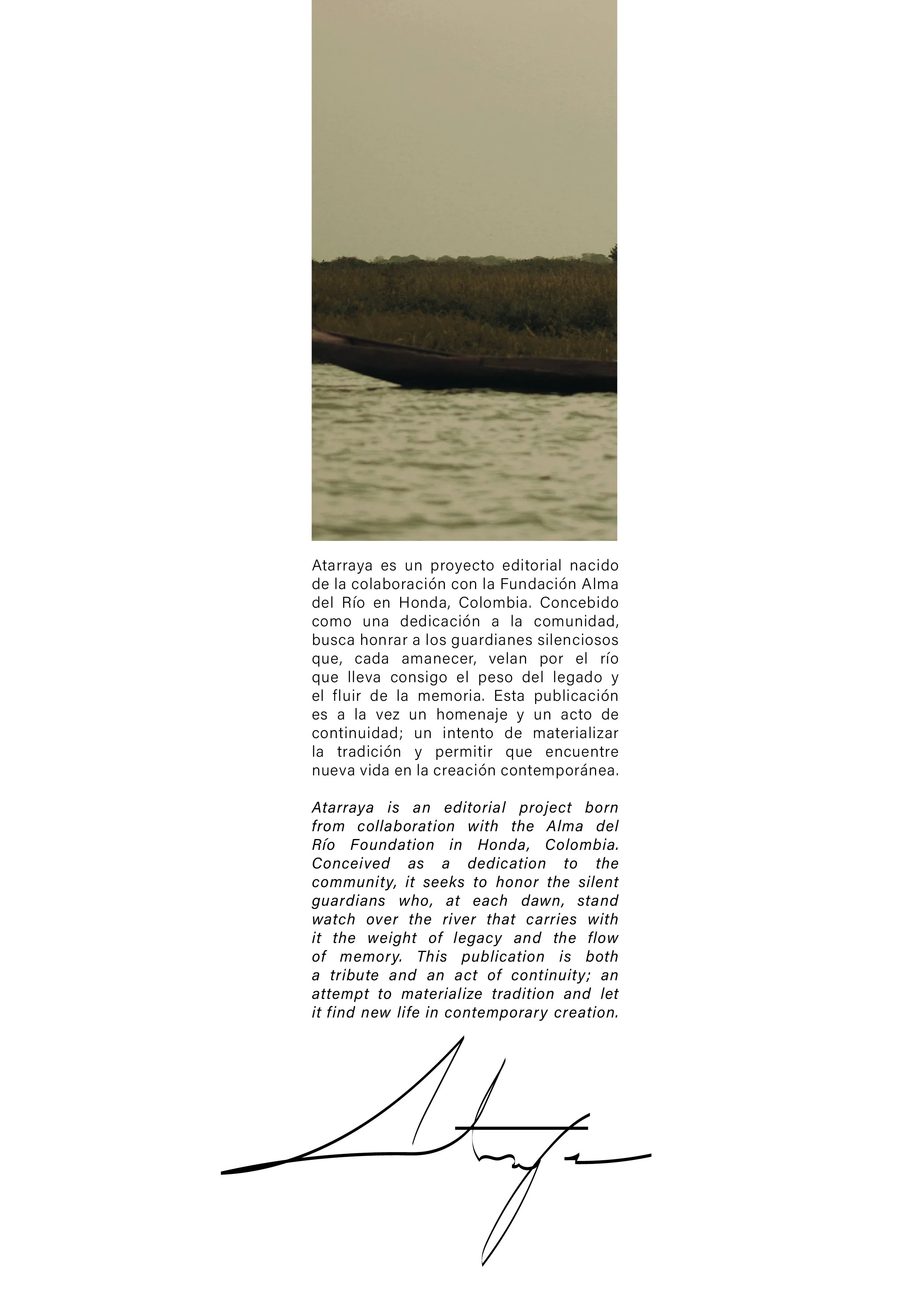

ATARRAYA

2025

INTERVIEW

Eduardo Lopez Ramirez “El Gavilán”

Date of Interview: 07/06/2025

Location: Honda, Colombia

Original Language: Spanish

Interviewee Profile

Profession : Artisanal Fisherman

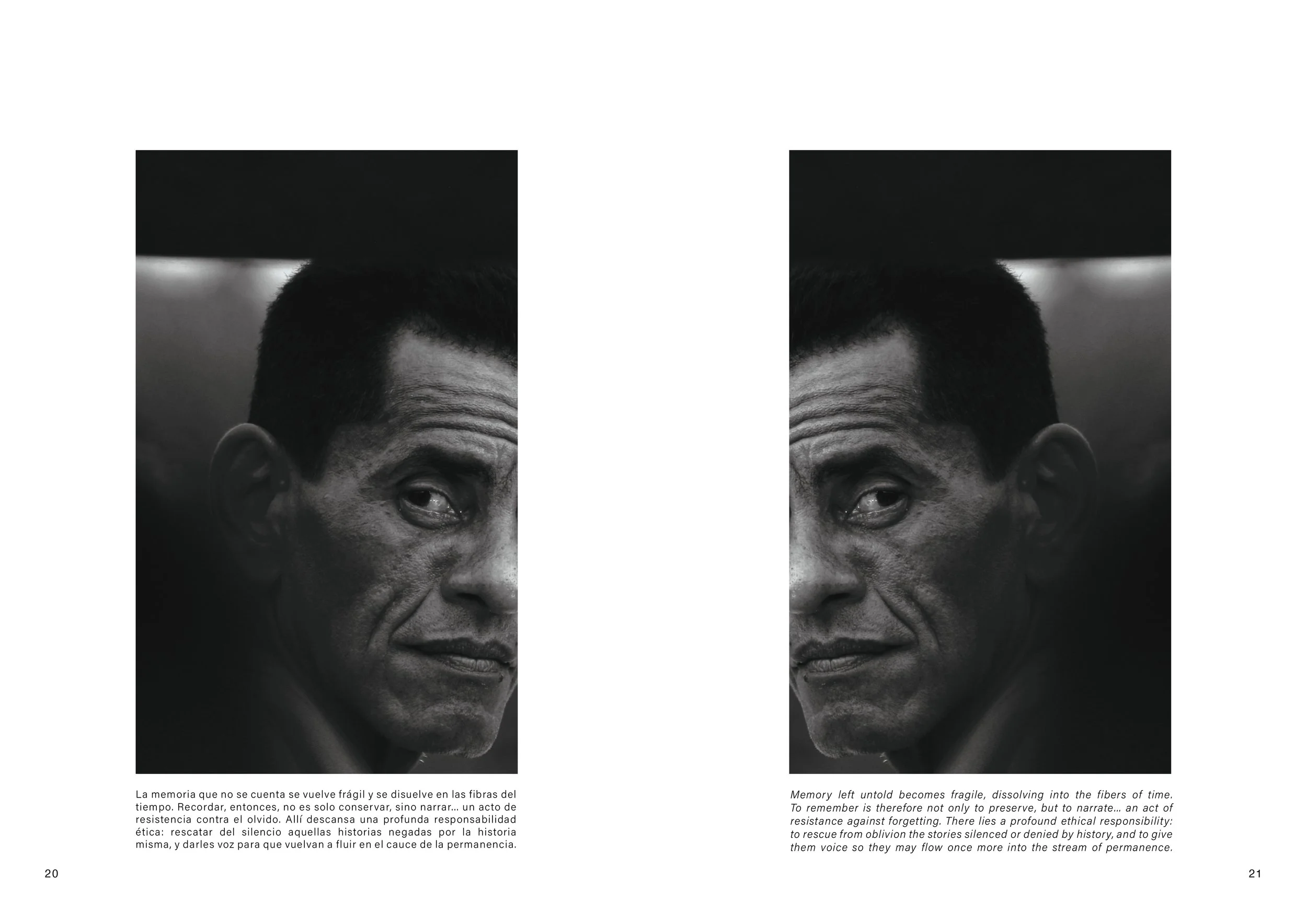

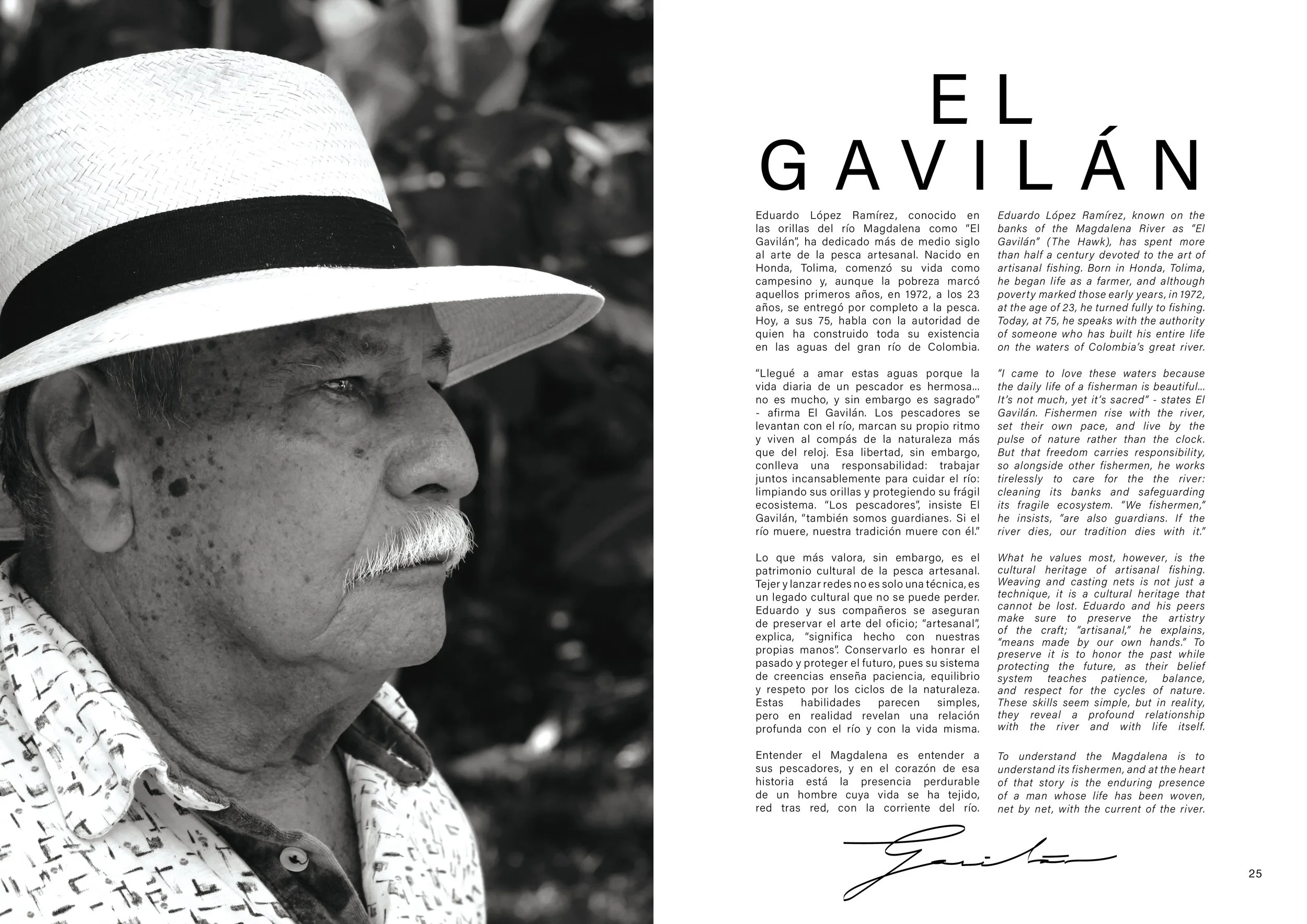

Background: Eduardo, locally known as El Gavilán, is a 75 year old artisanal fisherman from the Rio Grande de la Magdalena. Born in Honda, fluvial capital of the Tolima region in Colombia, he devotes his life to the art of fishing the way his ancestors taught him, and has a very strong endeavour to share his profession with the world.

Introduction and Purpose

The conversation with one of the most esteemed fishermen in Honda was crucial for this investigation, as there is nothing more raw than the first hand testimony of a man who lives in the Magdalena waters every day of his life.

Interview Transcript (Selected Extracts)

Researcher: Could you talk about how did you get started in this profession?

Interviewee: I started this trade when I was 23 years old. I was a farmer for the first part of my life, and my parents and I owned a piece of land in the countryside. At the time, we were very poor, so but I began my life in artisanal fishing in 1972, and now I have more than 55 years of experience and can confidently say that I supported my family thanks to the Magdalena River.

Researcher: How would you describe the daily life of a fisherman?

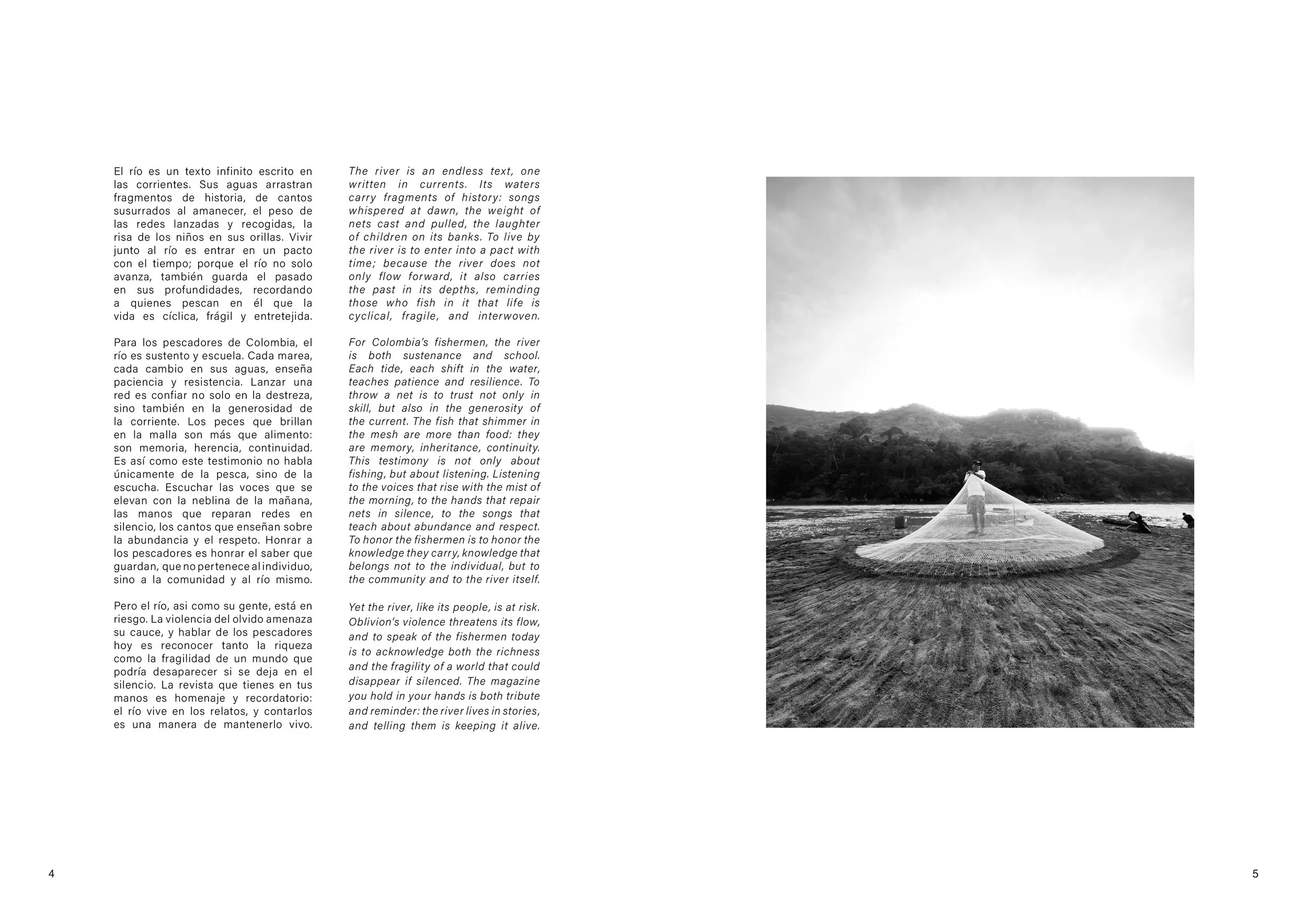

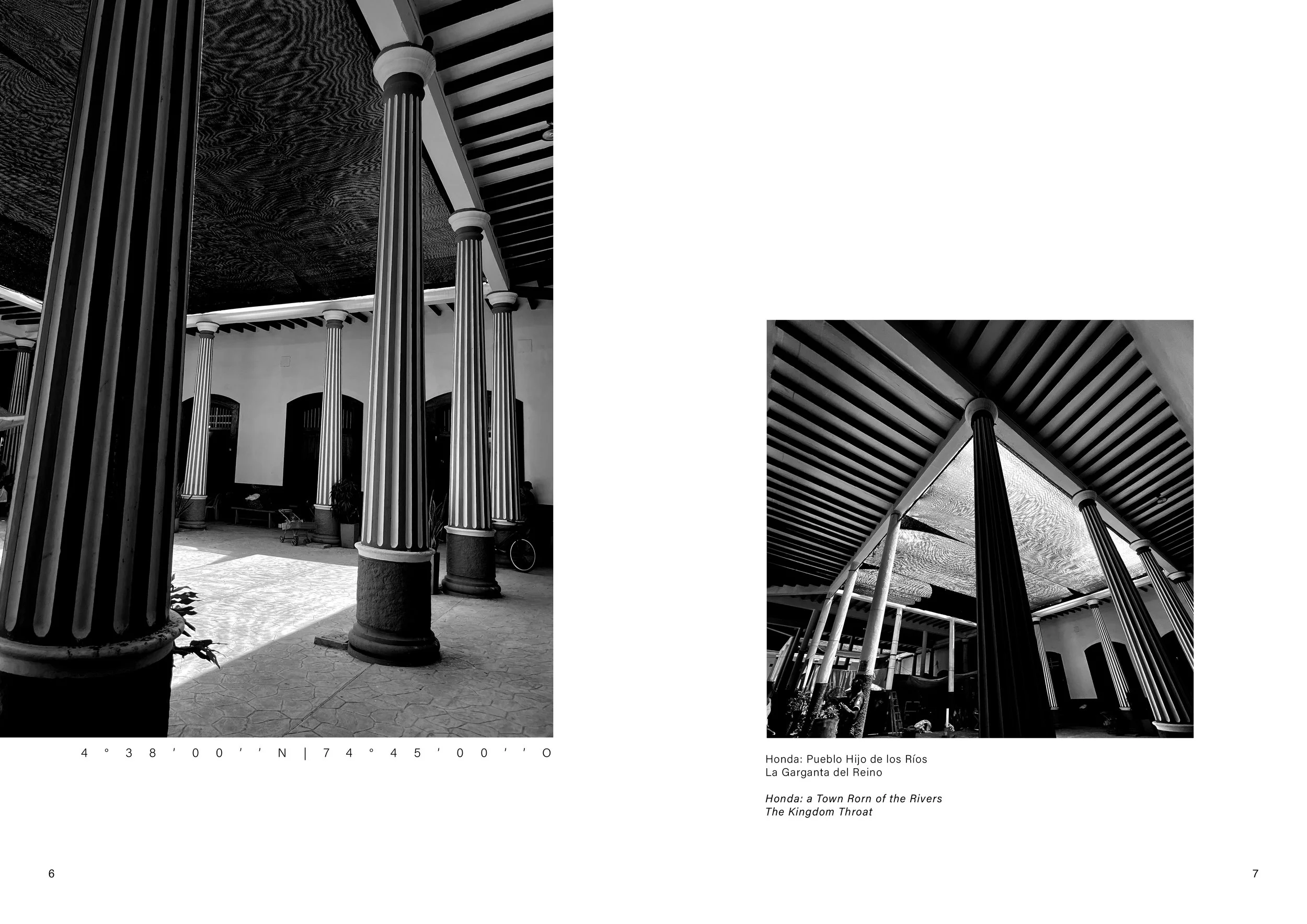

Interviewee: The daily life of a fisherman on the Magdalena River is very rewarding, as its 1,447-km-long waters feed hundreds of families. We, as fishermen, take care of it, and on behalf of the municipality, we do proper work, both fishing and caring for the flora and fauna. I came to love these waters because the daily life of a fisherman is beautiful. You see beautiful views at sunset, the breezes, the animals, the birds, you find crocodiles, alligators, you find yourself at the water’s edge drinking water in the summer, you hear different kinds of birds. It’s not much, it’s sacred. Let’s say the Magdalena is a business for us fishermen. We go fishing, we get up to go to work whenever we want, we come to sleep whenever we want. We fishermen live an independent life.

Researcher: Don Eduardo, what does artisanal fishing mean to you, or what do you consider it to be? You know that UNESCO recently declared artisanal fishing and all the customs of the Magdalena River as intangible heritage of humanity. Tell me, what makes up all this heritage? Everything that happens on the Magdalena River, artisanally speaking.

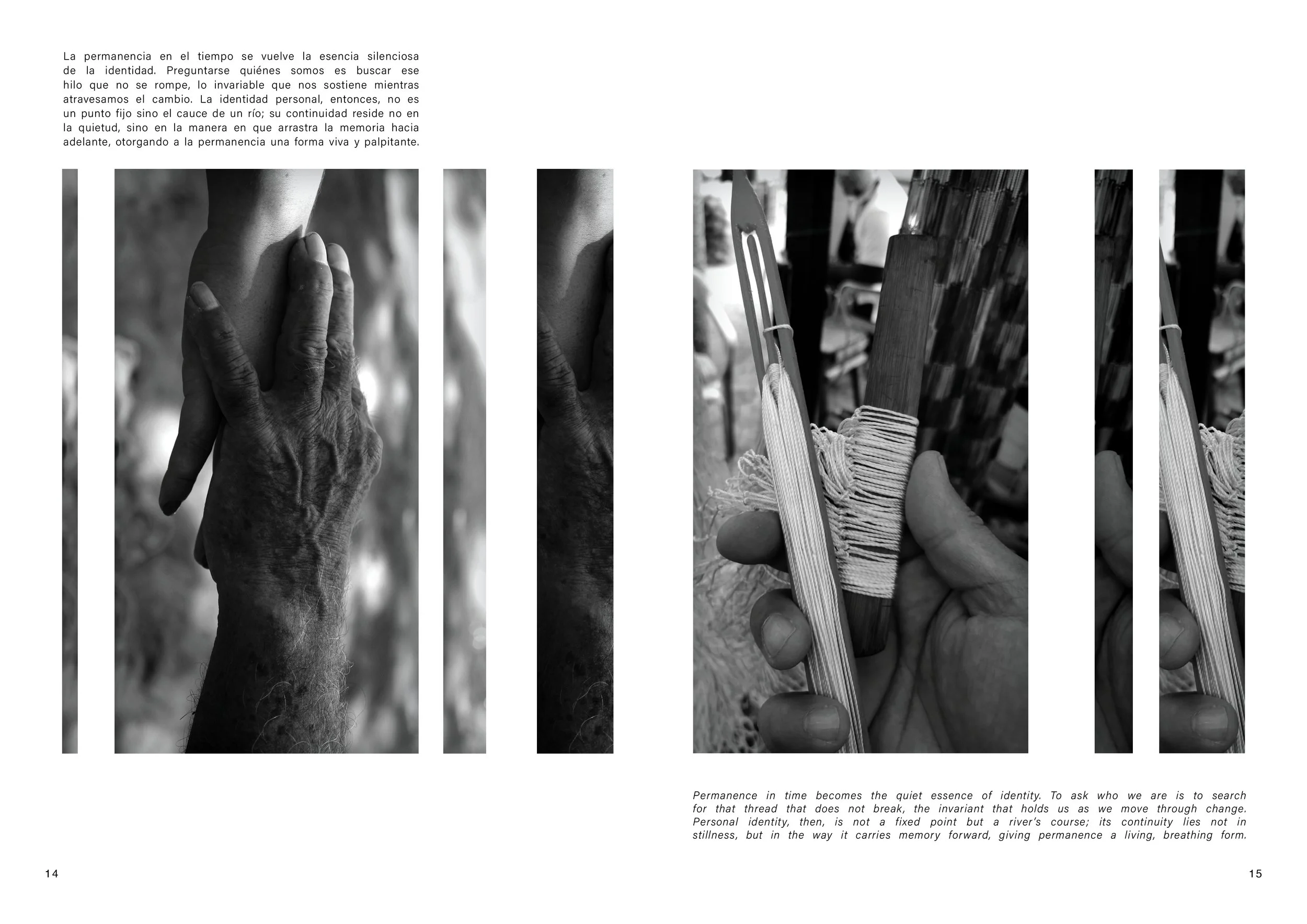

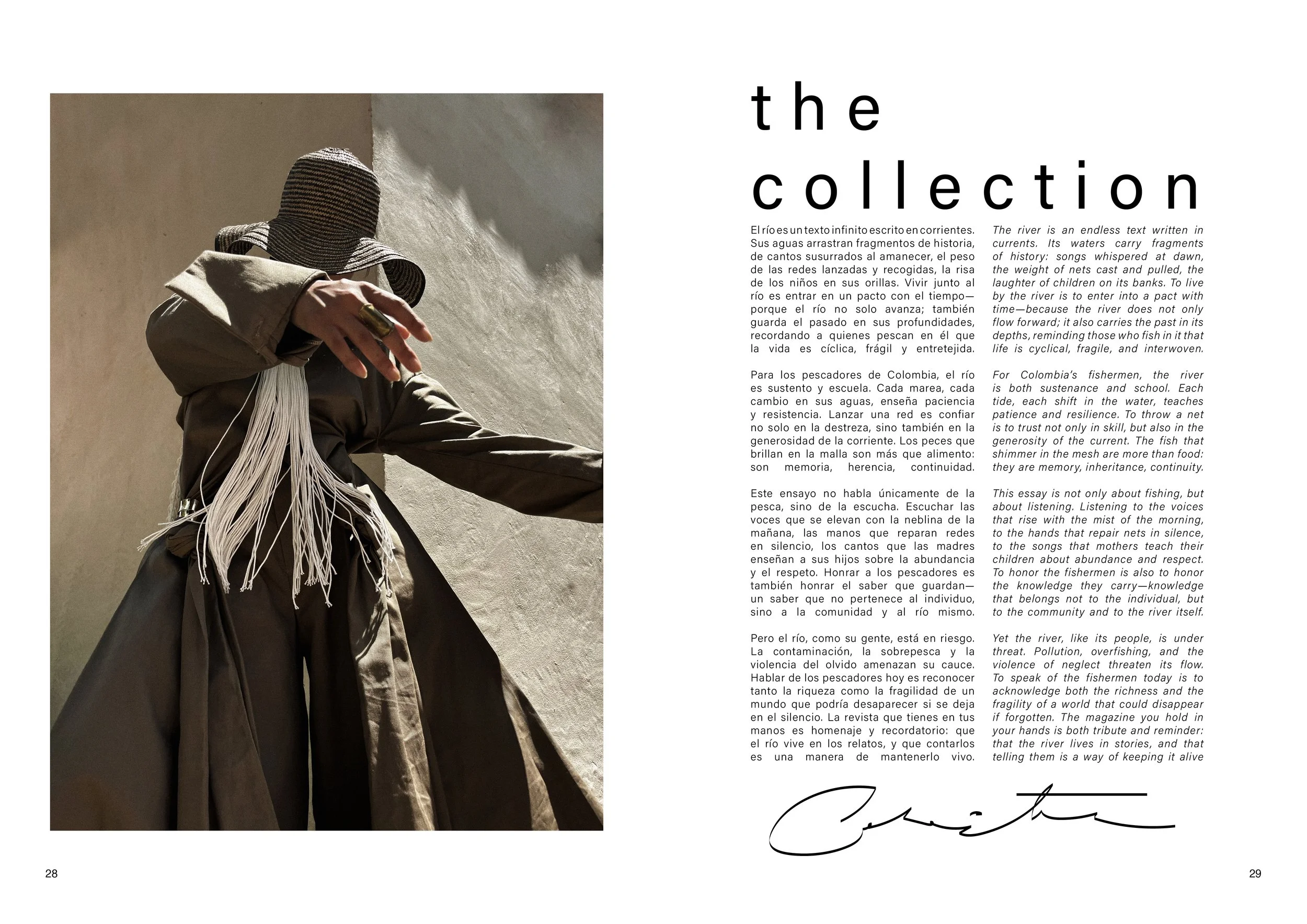

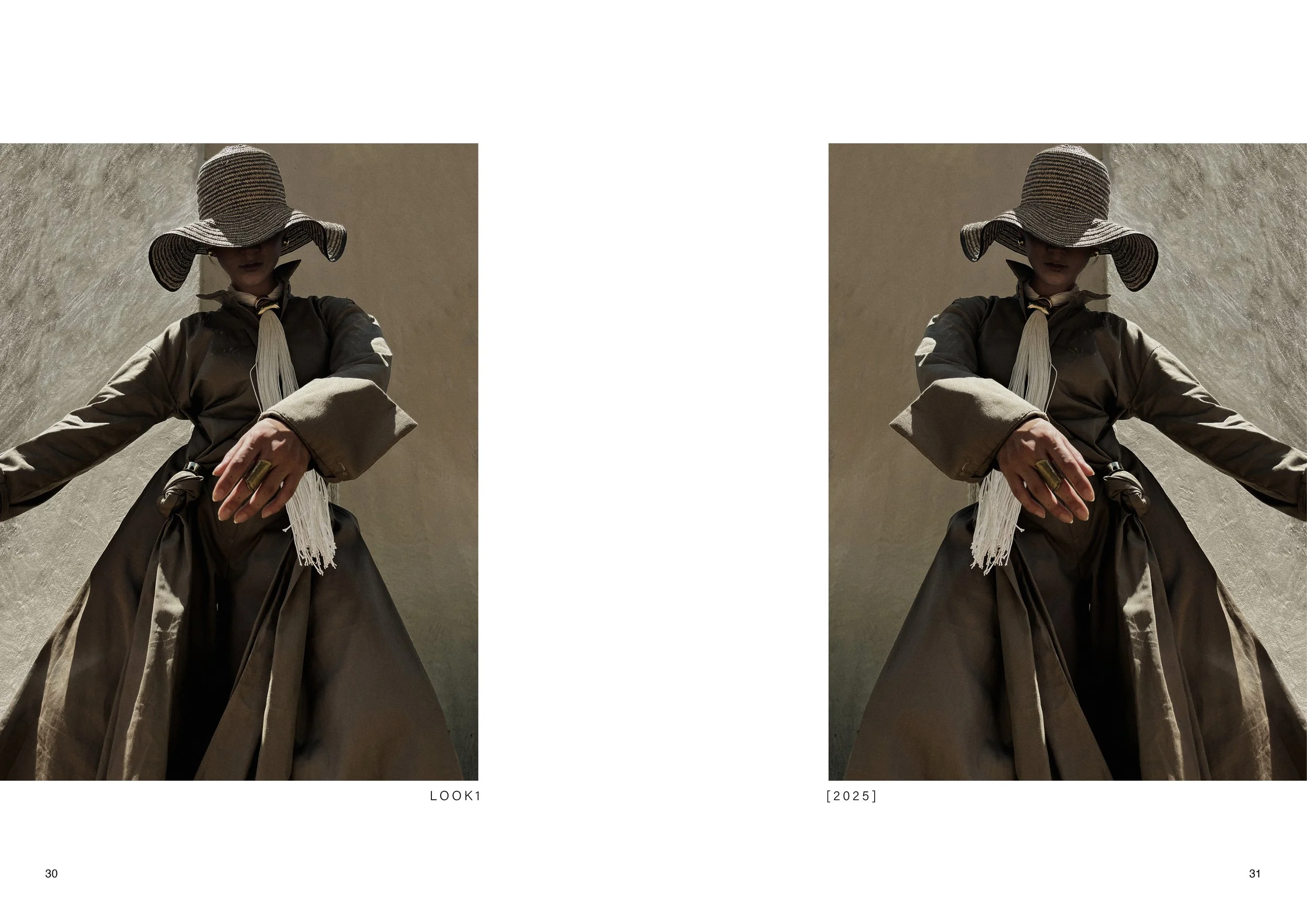

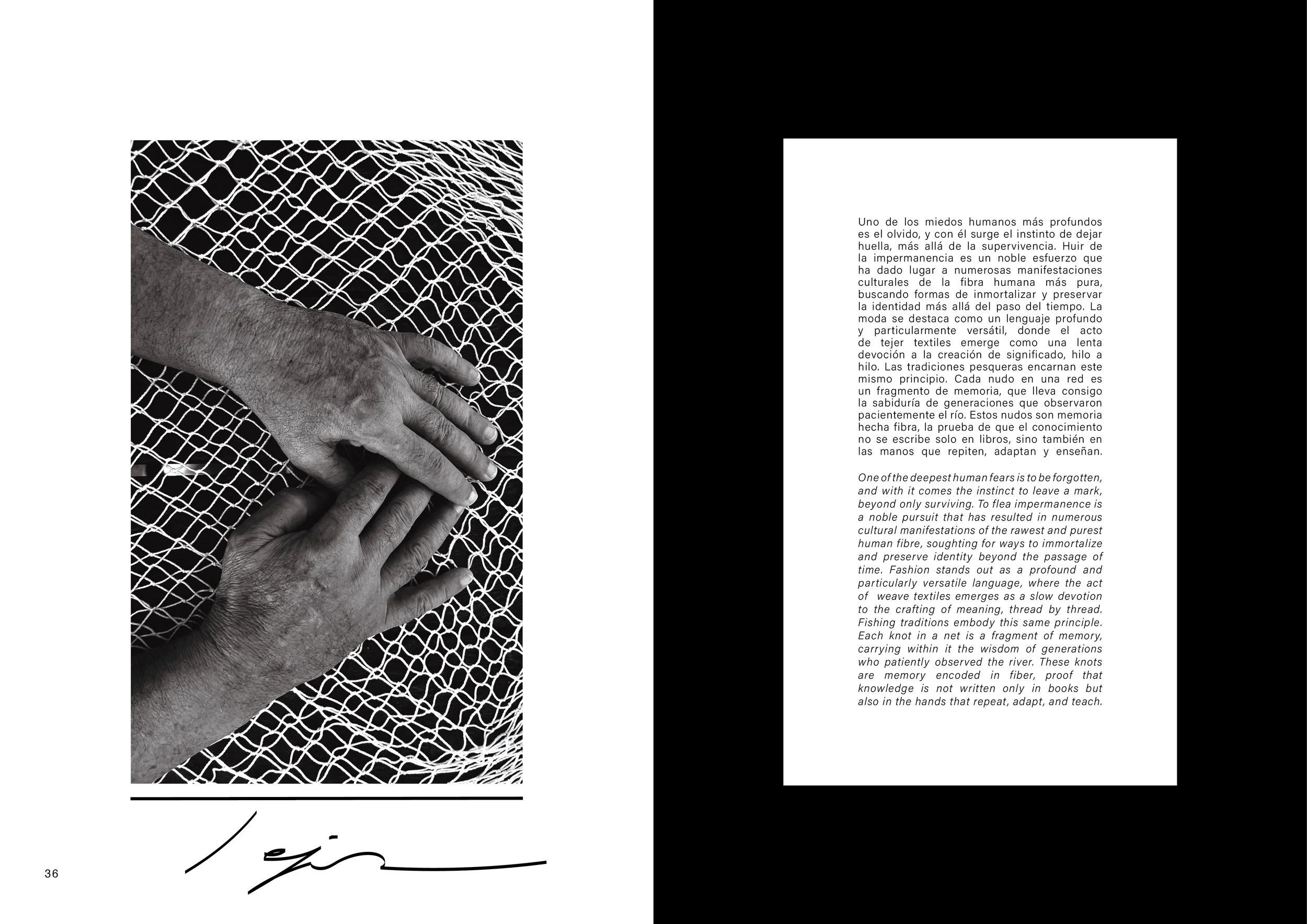

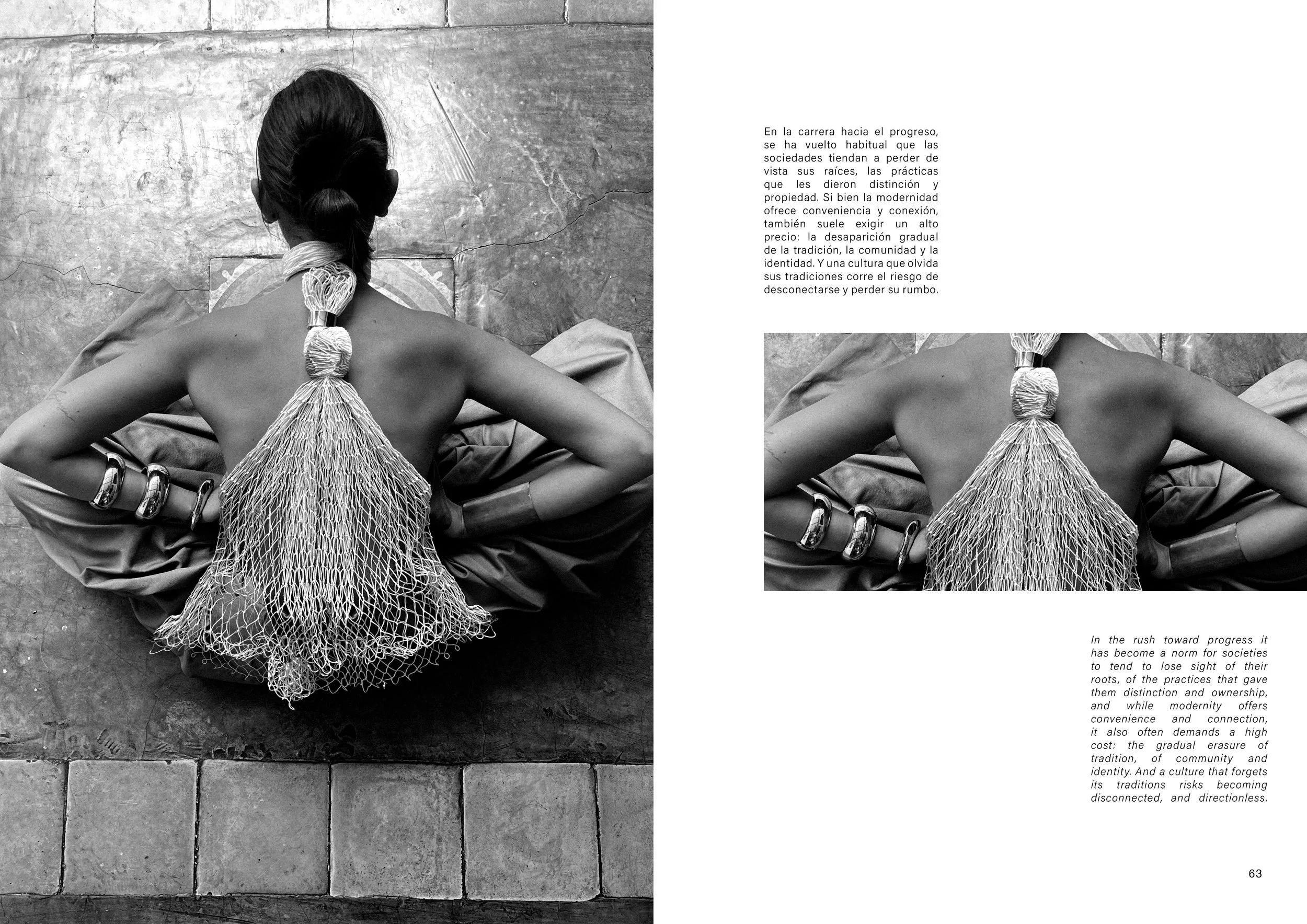

Interviewee: The cultural heritage of the fisherman is truly what we want, and that is for the art of fishing, which is an intangible heritage that we must not lose, to remain in the culture of our ancestors. What we have to do is strive to preserve the culture of the fisherman. For us fishermen, and at the national and global level, the fisherman is very instrumental, very associated, very important in the lives of countries, of nations, of the united people who live in our countries. How beautiful it is that in any department of our country we have different cultures. Right now, in Magdalena, we are a culture of artisanal fishermen. Why are they called artisanal? Artisanal because we make our own tools, which we use to fish. The fishing operations are the fishing that we do. Nowadays, there are machines that weave this. They’re not taking away the work, but we like to work this way because it’s tailored to your needs and your pleasure. We make different kinds of cast nets.

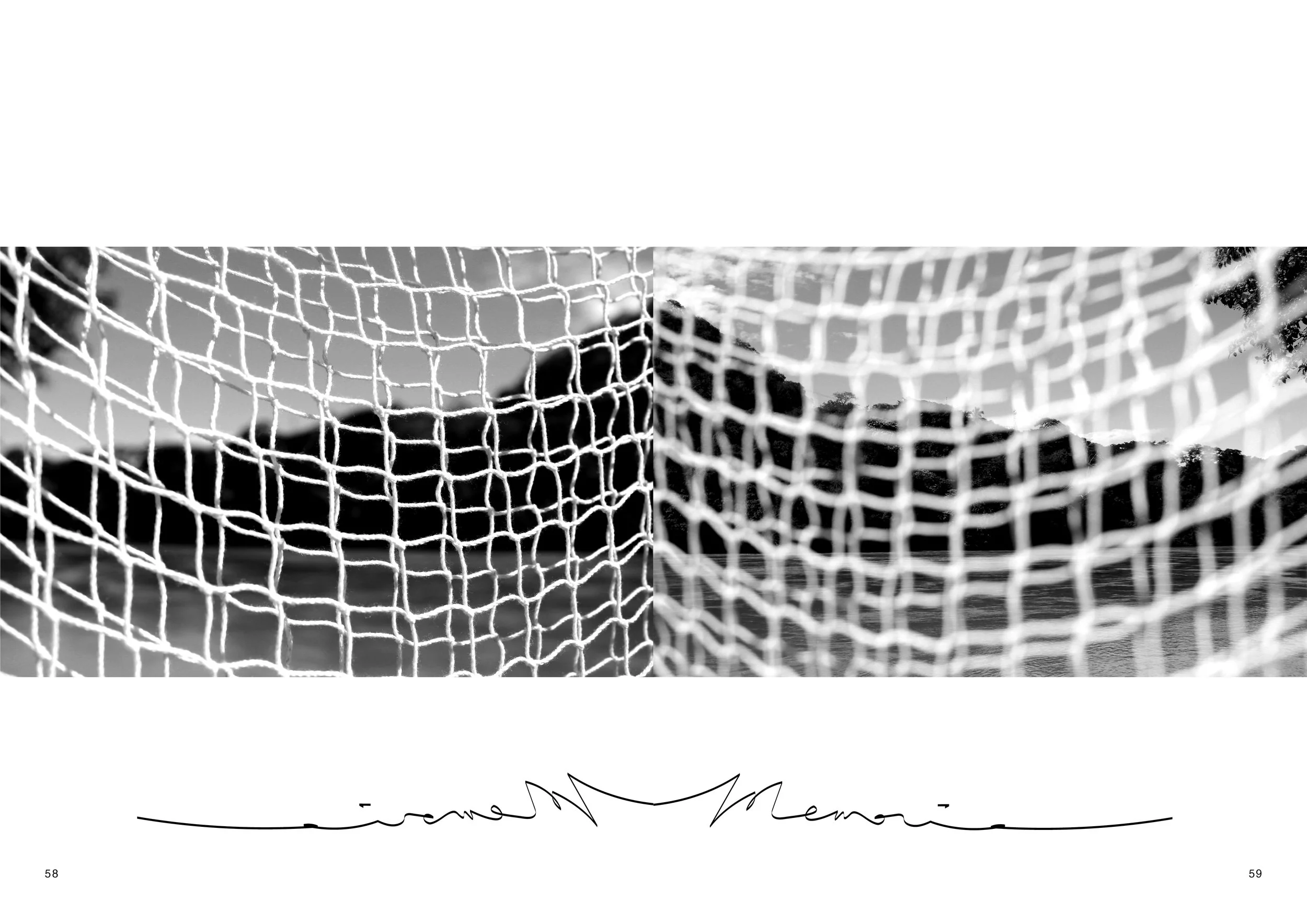

Researcher: Tell me, for example, about a regular cast net (Atarraya), what technique do you use, what type of threads, how long it takes to make?

Interviewee: This cast net takes a month to set up. If you’re a good weaver, it takes a month to get it from head to toe.

Researcher: What must be done to preserve the example of our life and culture? Because today, our culture at Honda has sort of faded away.

Interviewee: What are the important figures like the presidents of the associations, the municipality, the national government, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, UNAD doing? They’re fighting to ensure that we don’t abandon the cultural project, that we don’t leave, that the fishing culture isn’t lost. Look, Honda is beautiful. Honda is a source of fishermen, on both sides of the banks, where the high water reaches, people live, enjoy, and take fish to all parts of the country.

Researcher: What do you think are the challenges facing the fisherman lifestyle today?

Interviewee: We fishermen, all of us, suffer, because we all suffer in this country, because to live anywhere in the world, in any country, we have to pay to live, because nothing is free, everything has to be paid to live. If you live in a house, you have to pay rent; if you own a house, you have to pay taxes; if you want electricity, you have to pay; if you want water, you have to pay; if you own anything, we have to pay; if someone picks up a bag of garbage, we have to pay. The fishermen in Honda, or on the banks of the Magdalena River (and I’m talking about Colombia’s artisanal fishermen), both maritime and inland, all face economic problems due to the challenges in fishing areas nationwide. We Colombian fishermen, more than 346,000 registered with the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, are at risk of losing our beloved profession, but the truth is that everyone experiences scarcity at times, but we have to take advantage of them when we have abundance.

Researcher: Don Eduardo, why do nets have different weaves?

Interviewee: Because they are for different kinds of fishing

Researcher: What is the main characteristic of the Atarraya?

Interviewee: This is the atarraya (cast net), so this is what a real fisherman uses. This is the culture. Here we see the difference in the fisherman’s culture, our ancestors taught us to work with it.

Viviana Gomez Cardozo

Date of Interview: 15/08/2025

Location: Honda / Bogota

Original Language: Spanish

Interviewee Profile

Profession : Manager and founder of the foundation Alma del Rio

Background: Viviana is a young entrepreneur who, after completing her university degree, decided to return to her homeland with the intention of making a difference.

As a result of her strong social vocation and love for the community where she grew up, she decided to start Alma del Rio, a non-profit foundation that supports all aspects of the needs in Honda. From animal rescue to firefighter training, Viviana has empowered and helped countless community members, but her most notable work has to do with her support for the fishing community. Through visibility, she believes the art of fishing can be a source of income not only through food but also as a cultural activity.

Introduction and Purpose

The interview with Viviana was conducted with the intention of learning from the perspective of someone who dedicates her life to supporting the fishing community, aligning with the objective of this thesis. Furthermore, all proceeds from the magazine will go to her Alma del Río Foundation.

Interview Transcript (Selected Extracts)

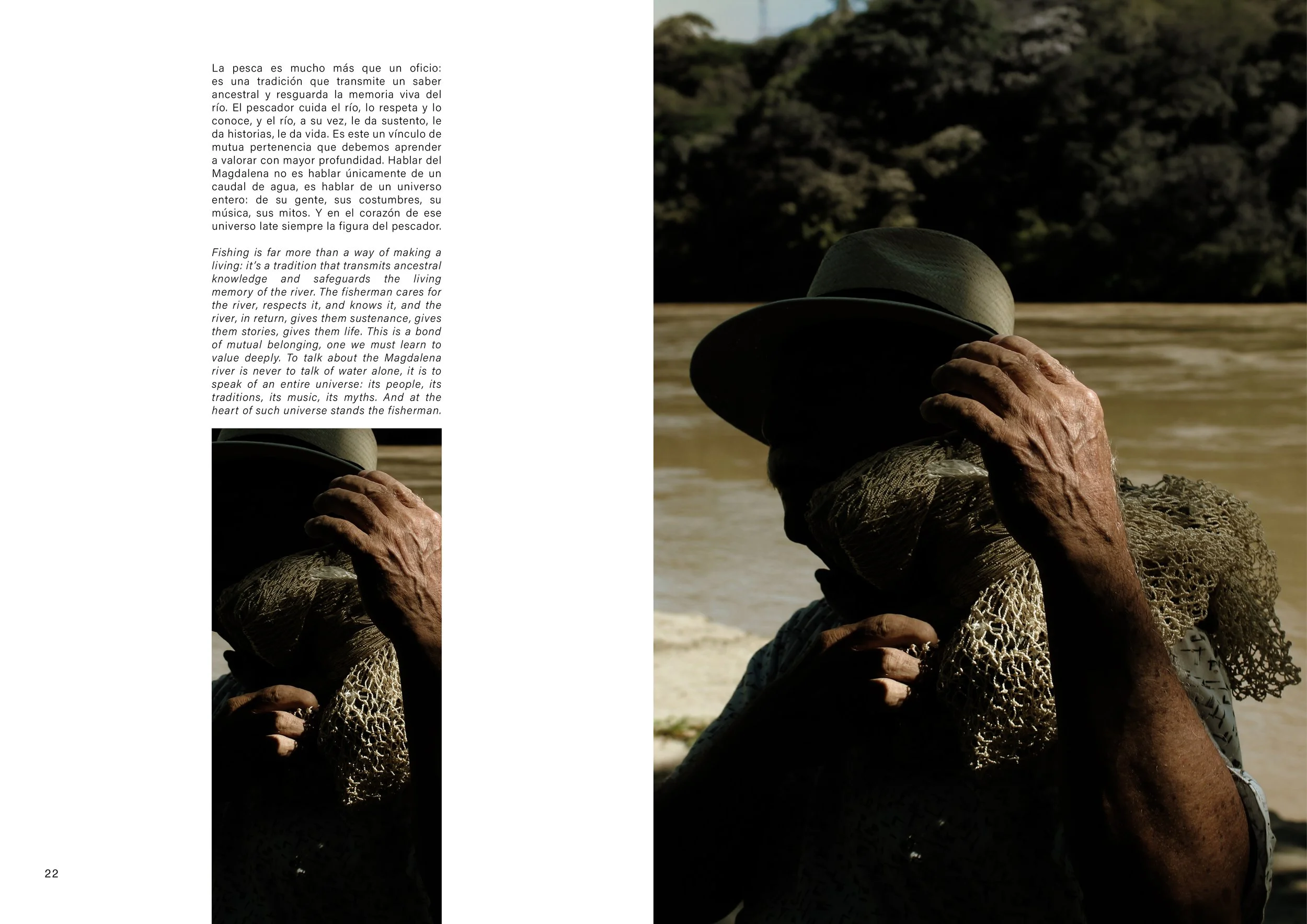

Researcher: From your perspective, talk about the fisherman’s job

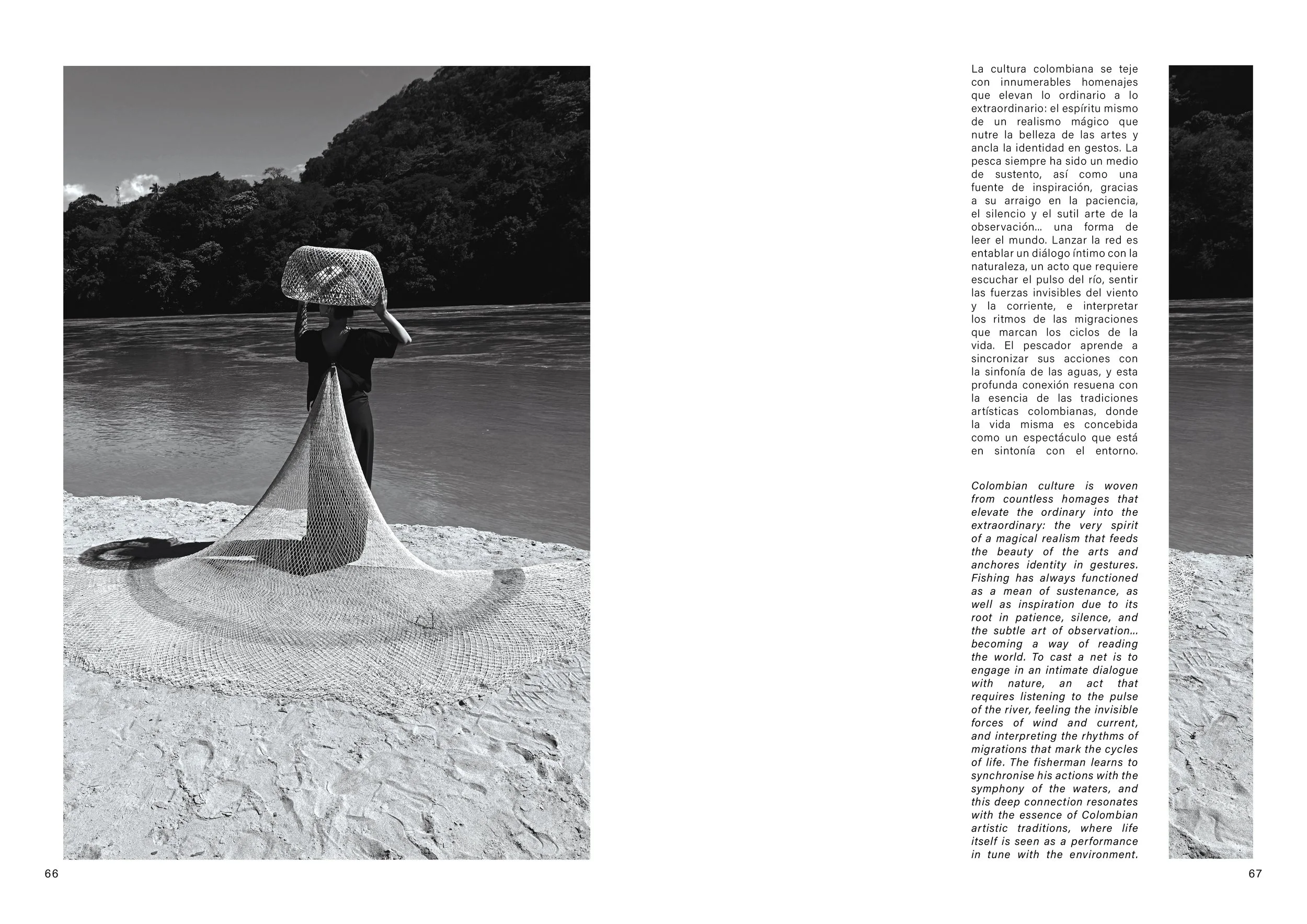

Interviewee: There’s much to be said about the fishermen of the Magdalena River. I think the fishing trade is much more than a way of making a living. It’s already becoming a kind of tradition, a living heritage. It’s like a knowledge passed down from generation to generation and truly preserves the memory of the river.

Researcher: What is the importance of honoring the work of fishermen?

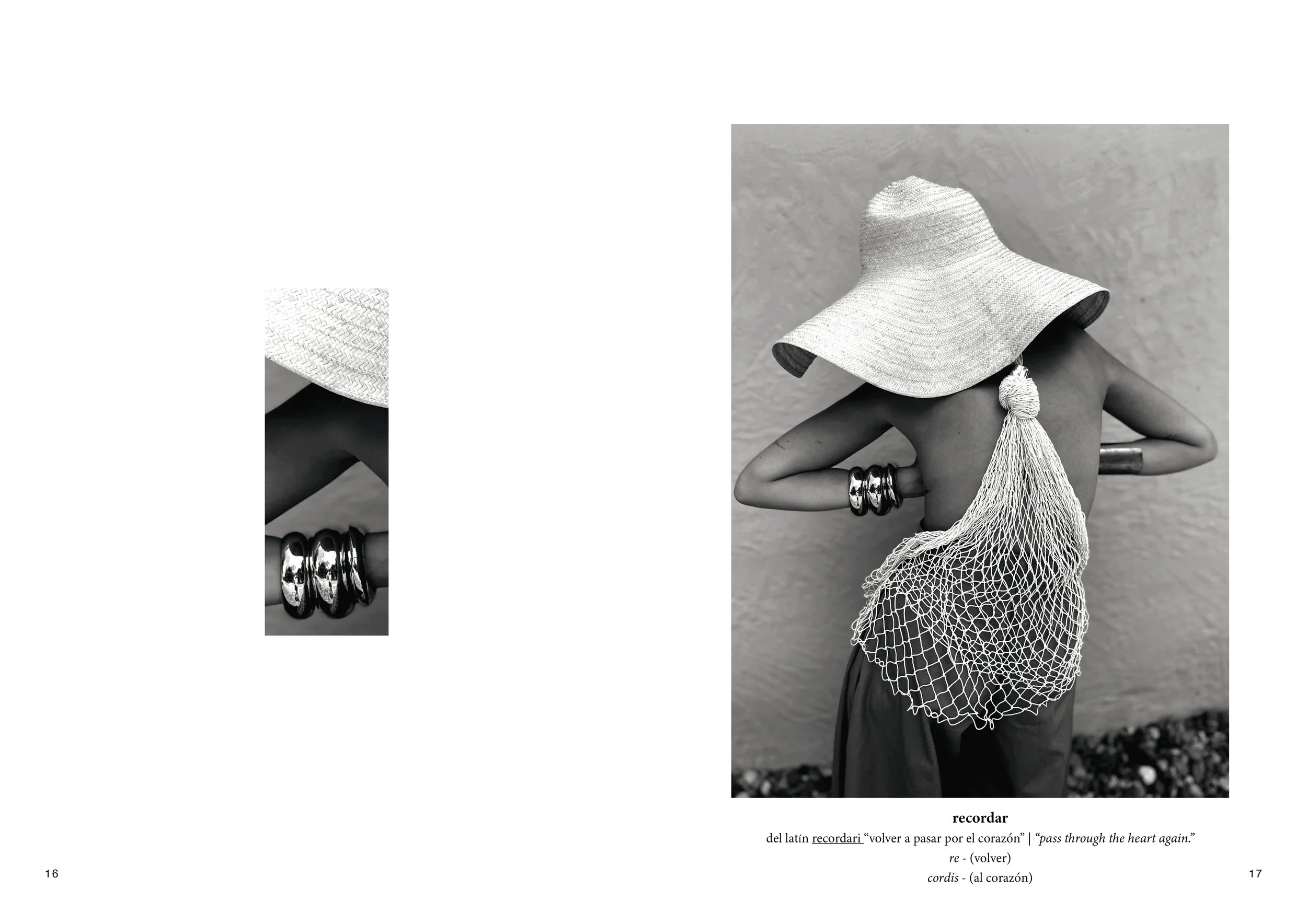

Interviewee: When one honors the work of fishermen, one is actually also honoring the role they play as guardians of an invaluable cultural and environmental heritage. They not only take food from the river, but they also preserve artisanal techniques, stories, legends, and ways of understanding the world that are part of the identity of riverside communities.

Researcher: Explain a little about your perspective on the mystical spirit of the Honda fisherman.

Interviewee: It’s always very interesting how, when you talk to them, the tales of the moán, the patasola, or the stories of ghosts who cross paths in the early mornings come up. But of course, the moán is the river’s most powerful character, almost the symbol that connects people with the magic and sacredness of those waters. The fisherman is something of a storyteller, something of a popular sage, because between the nets and the oars, he preserves memories. These stories aren’t in books; they’re in the words passed around in the canoe or on the shore, while they wait for the fish to bite. Furthermore, this belief system teaches patience, respect for the cycles of nature, for closed seasons, for the moon and its changes. These skills seem simple, but in reality, they reveal a profound relationship with the river and with life itself.

Researcher: How would you describe the fisherman himself?

Interviewee: I would say that the fisherman is like a bridge: between the river and the family table, between nature and culture, between the past and the present. And if we don’t preserve this tradition, we risk losing a whole world of knowledge. That’s why it’s key to raise awareness that fishermen aren’t just “those who work on the river,” but rather those who keep alive practices that connect us to our history as a country. The Magdalena River has always been the backbone of Colombia, and fishermen are the ones who best understand its pulse, its secrets, and its changes. No one can read the color of the water, the current, or when the river is swollen.

Researcher: Why is it important to preserve said tradition?

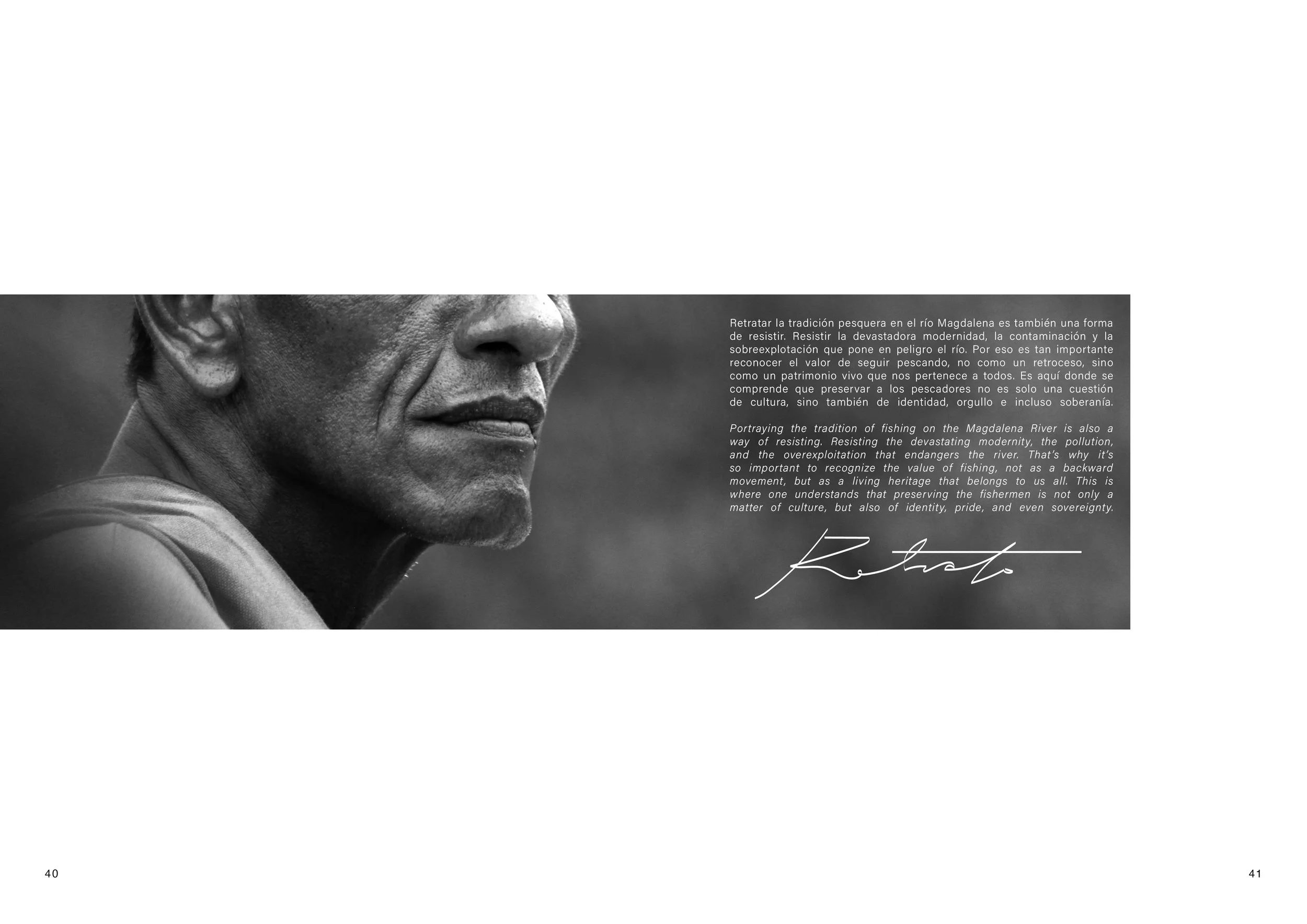

Interviewee: I think preserving the tradition of fishing on the Magdalena River is also a way of resisting. Resisting the devastating modernity, the pollution, and the overexploitation that endangers the river. Because, of course, it’s not easy to be a fisherman these days. Many young people prefer to move to the city, and the profession risks becoming only for older people. That’s why it’s so important to recognize the value of continuing to fish, not as a backward movement, but as a living heritage that belongs to us all. We should also consider that, when we support fishermen, we are supporting the food security of riverside communities. River fish is part of the diet, part of the flavor of the region. What would a festival be without its fish stew, without the bocachico sancocho? This is where one understands that preserving fishermen is not only a matter of culture, but also of identity, pride, and even sovereignty.

Researcher: What would you say is the most beautiful thing about the relationship between the river and the fisherman?

Interviewee: I believe the river and the fishermen need each other. The fisherman takes care of the river, respects it, and knows it. And the river, in turn, gives them sustenance, gives them stories, gives them life. It’s a two-way relationship that we should learn to value much more. In the end, when one speaks of the Magdalena, one cannot speak only of a river. One speaks of an entire universe: of its people, its traditions, its music, its myths, and at the centre of all of this is the fisherman.

Researcher: What surprised you most about starting to work with the fishing community?

Interviewee: At first, one of the things that surprised me most was seeing Eduardo. He’s been fishing for over 55 years, and of course, that experience shines through in everything he says. Over the years, he’s witnessed firsthand how overfishing and pollution have affected the river. He told me that we used to see huge schools of fish, and now the number of fish has decreased dramatically. You listen to him and understand that it’s not just nostalgia, but a real wake-up call about what’s happening. He insists that it’s not just about fishing, but also about learning to value the river. He always says that being a fisherman means being a guardian, taking care of what feeds us. That’s why, along with others, they clean the banks and even the water. They don’t do it because someone orders them to, but because they know that if the river dies, their tradition dies too.

Researcher: What are the aspects surrounding fishing that you have been able to identify through your work?

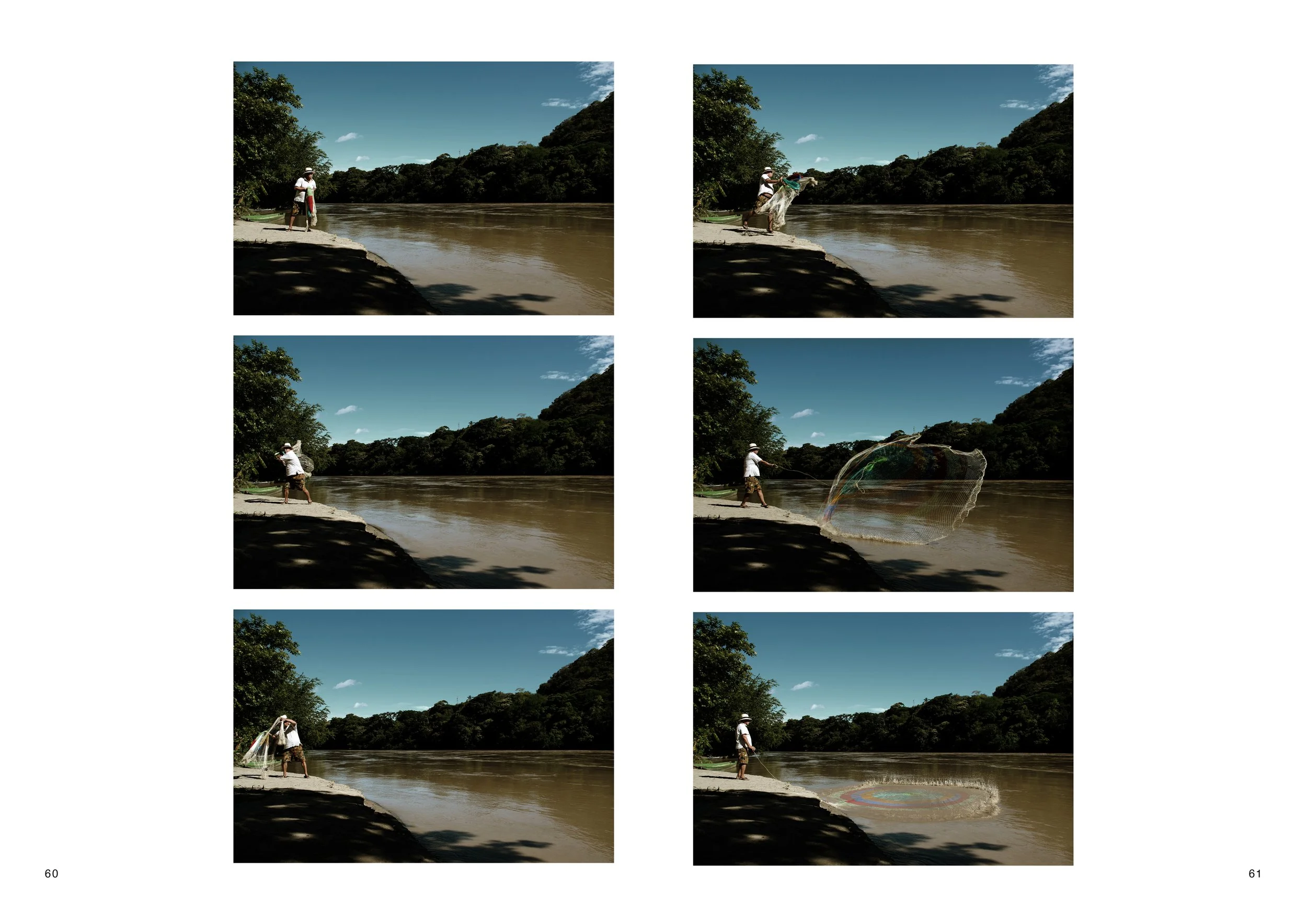

Interviewee: Surrounding that life on the river are also all the artisanal aspects, such as weaving nets and casting nets. You don’t learn that in school; you learn it by watching and practicing from childhood. With Eduardo, you understand that fishing is much more than a trade; it’s a whole way of life. He lives it as if every fish and every net were part of his personal story. It’s beautiful to see how he teaches young people not only to fish, but also to respect it. Ultimately, what he conveys is that caring for the river also means caring for the memory and future of the community.

Researcher: How important do you think it is to pay tribute to this profession?

Interviewee: So, paying homage to them is fundamental, and when I say them, I mean both men and women. Because, of course, what you see most is the men in the canoe, with the nets and the fish, but behind all of that are also the women. They are the ones who manage the administrative side, the ones in charge of trading, selling the catch, and negotiating in the market. In reality, the money is primarily handled by women, and that speaks to a teamwork that often goes unseen. So, paying homage is recognizing that shared effort, that chain of hands that keeps the tradition alive. It’s a way of thanking them for keeping a model alive that reminds us where true wealth lies. Because wealth isn’t just about accumulating, but about living off natural abundance in a respectful way. The fisherman knows that only what is necessary is extracted from the river, never in excess, always in balance with nature. And this teaching seems to me to be key for today’s life, where this principle of respect is often forgotten.

Researcher: Where does the essence of your foundation come from?

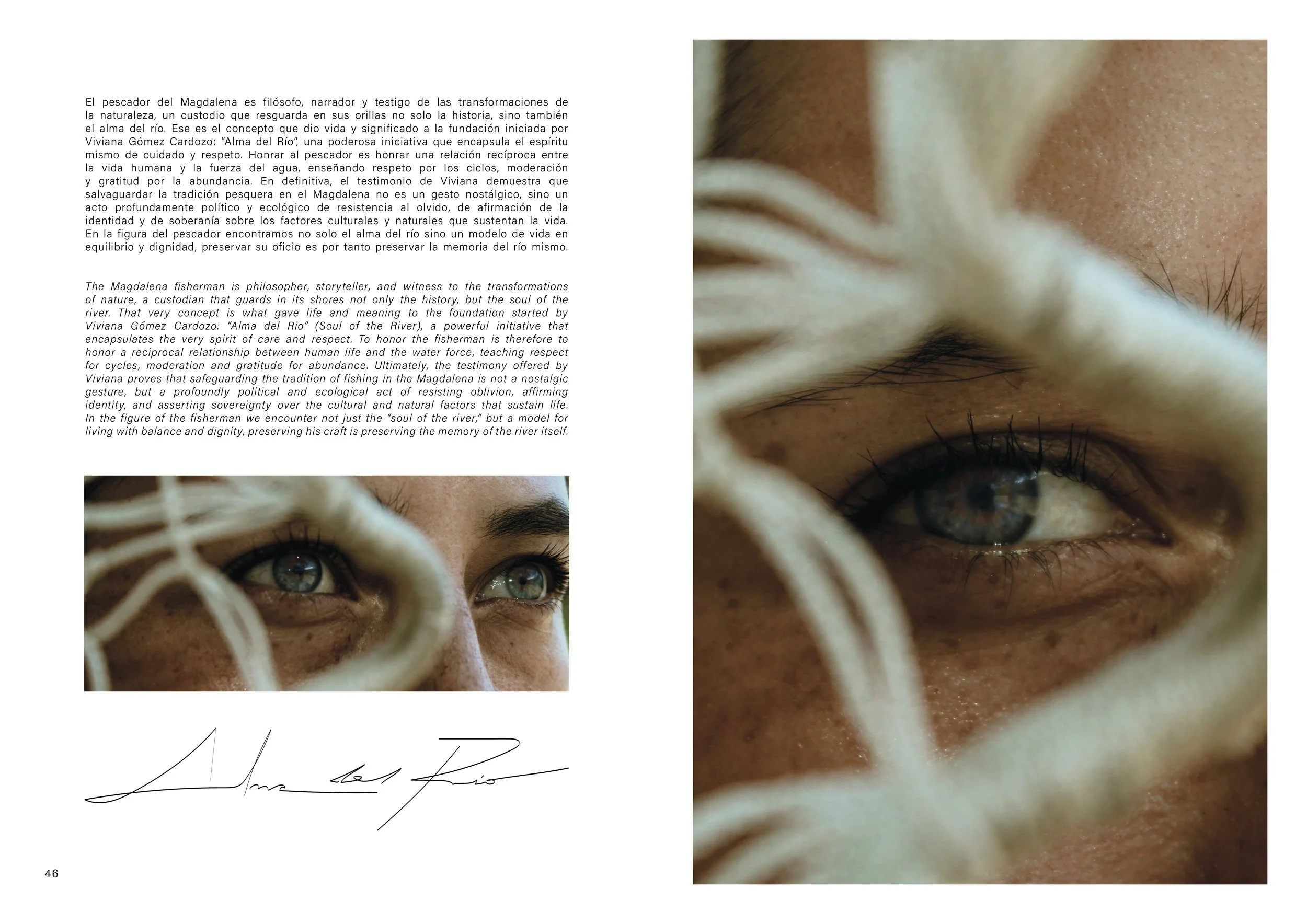

Interviewee: In essence, I believe that the Magdalena River fisherman is a custodian, someone who guards not only the history but also the soul of the river. That phrase, “Alma del Rio” (the soul of the river), is very powerful for me because it encapsulates the meaning of artisanal fishing. It’s not just a profession; it’s a way of relating to life, to the community, and to memory.

That’s why I chose “Alma del Rio” as the name of my foundation. I felt like no other name could better capture that spirit of care and respect. Every time I say it, I feel like it’s a reminder: the river isn’t just a resource; it’s a living being with whom we coexist. And those who best understand that spirit are precisely the fishermen and women. They are the ones who keep that deep connection with the water alive every day. So paying tribute is also a commitment to continue learning from them.

Ultimately, it means understanding that caring for the fisherman and his tradition is caring for the river itself.